The first time I used AI wasn’t anything spectacular; it was rather insignificant. Chat GPT wrote me four lines of copy filled with emojis for a LinkedIn post. I could undoubtedly have written something similar myself, but it was done in seconds instead of the fifteen minutes it would have taken me. That small saving of time masked the arrival of an overwhelming technological force that was coming to change everything. However, for me, the appearance of LLMs at that moment only meant that I would no longer have to strain my brain to write; a simple, poorly formulated prompt to ChatGPT could handle that part of my work for me, while I focused my efforts on other matters I considered more relevant.

This was how my relationship with AI began, and I would venture to say that something similar probably happened to you as well. It wasn’t a sudden revolution but a series of seemingly insignificant pseudo-prompts that, in a short time, began gaining ground in our daily processes.

Today, roughly two years later, ChatGPT has become an essential tool in virtually every office and smartphone in the world. The battle among AI agents is in full swing, with Claude, Grok, GPT, Gemini, Copilot, and others releasing increasingly powerful models at such a rapid pace that what was cutting-edge yesterday seems obsolete today. The AI revolution is very real; it has integrated into all sectors and into our homes, becoming an active part of our processes and decision-making. Perhaps what is truly relevant at this point isn’t the tool’s power, but how we relate to it: to what extent do we continue to apply our own judgment when evaluating its recommendations, or do we let speed turn its suggestions into prescriptions?

We have grown accustomed to delegating to immediacy and convenience, allowing productive efficiency to become almost the dominant criterion. In the following lines, I aim to explore precisely that tension: if it is no longer necessary to go through the effort to reach a result, what then remains of the value of the process itself? This is not about demonizing technology, but about determining whether the immediacy and convenience it provides are truly fully compatible with the human experience, or whether we must mediate to preserve spaces where slowness and effort still have an irreplaceable role.

Time as a Teacher

Throughout history, the execution of work has been a constant dialogue between our hands and our minds. That applied synchrony to a specific domain (cooking, developing software, carving stone, or building walls) and oriented toward solving problems inherent to that field is what we recognize as skill.

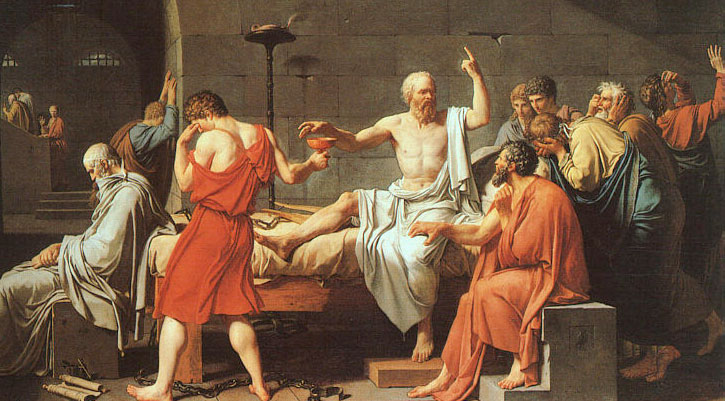

Work has always necessarily involved the transmission and assimilation of knowledge. For centuries, trades and skills have been taught from person to person, from master to apprentice, in an exchange that went far beyond data or mere instructions. Learning has always meant observing, imitating, asking, assimilating, and above all, sharing time and space with someone who has already walked that path. In this way, not only techniques but also criteria, values, and ways of understanding the world and work were passed down.

With the advent of digital tools, and now AI, this transmission has gradually begun to dissolve. It is no longer necessary for a mentor or master to teach us how to solve something, nor to dedicate time and effort to assimilate key concepts to carry out our craft: it is enough to ask an agent to give us the answer to our questions, to tell us what to do and how, without needing to understand the why behind each step. This new way of working undoubtedly allows us to gain speed, but we lose context. We get the what, but not always the why. The result we obtain may be functional, but perhaps we are skipping the deep learning that used to be inseparable from the process.

Sociologist Richard Sennett, in The Craftsman, writes about the immense personal satisfaction of doing a job well for the simple sake of doing it well. Craftsmanship, according to Sennett, “designates a durable and basic human impulse, the desire to do a task well, and nothing more.” There is an inevitable sense of pride that overwhelms us when we produce something we understand from the inside, something we have worked hard on, something we have wrestled with for hours, days, or even months. This process is by no means easy; it is often cumbersome, heavy, and even frustrating in moments of doubt or uncertainty, but it is a necessary process. A process that shapes us as much as we shape our work.

As Neil Postman warns in Technopoly, each new technology redefines not only what we do but also what we stop doing and, with it, who we are. AI frees us from slowness, but it is precisely in that slowness that knowledge is embodied and transmitted. By eliminating it, it is easy to ask whether we are amputating the very root of what we call learning.

The Erosion of Judgment

From a strictly productive perspective, the instantaneity that AI offers us is an improvement. Thanks to new models, we can reduce the time required to perform certain tasks to practically zero. The effort required to complete them has also been reduced, and in some cases, even eliminated entirely. It sounds idyllic, but like many things, it has negative consequences. As Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee warn in The Second Machine Age, technological progress is not always synonymous with human progress. Automation can free time and energy, but it can also untrain our skills if we delegate to machines what only strengthens through exercise.

An MIT study, Your Brain on ChatGPT, concludes that the more we delegate to AI, the less we exercise deep mental processes such as organizing ideas or constructing an argument. This produces what is known as “cognitive debt”: an accumulative loss of the ability to think for ourselves, imperceptible at first, but with a real long-term impact.

It might therefore seem that this clear improvement in productivity is, in reality, a short-term gain with long-term loss. What is the value of being faster, more precise, and efficient if we have not actually improved ourselves, but the improvement is only an illusion generated by data-processing models? To what extent is all this technological progress, all this productivity, worth it if it comes at the expense of our critical and rational capacity?

But AI is not just a threat to reflection; it also allows us to do things that we could not achieve individually. Analyzing enormous volumes of data, detecting invisible patterns, anticipating risks, optimizing complex systems, or supporting medical diagnoses are examples of capabilities that expand and enhance us. Well-used, AI does not replace our intelligence: it extends it.

Beyond what is human

The history of humanity is, to a large extent, the history of how our tools have expanded what we are capable of doing. In prehistory, the first axes and spears allowed us to hunt large prey; later, the wheel multiplied our strength and transportation capacity; the printing press expanded our collective memory; and satellites extended our gaze beyond the imaginable.

Today, artificial intelligence has not only lightened our daily tasks but has also opened new possibilities that were completely out of reach. We can now see patterns invisible to our senses, allowing us to detect diseases before the first symptoms appear, saving thousands of lives; advances in exploring our planet and the universe accelerate thanks to the ability to process vast amounts of data beyond human comprehension; culturally, AI can restore artworks, translate dead languages, or digitally reconstruct ancient cities; it can optimize energy consumption and emissions by regulating electrical grids in real-time or adjust urban traffic to prevent congestion, among many other significant achievements.

AI does not merely replicate what we already did; it has expanded the horizon of what we can achieve, taking our capacities beyond strictly human limits. But the more we depend on it to see, understand, or decide, the more we risk being unable to see, understand, or decide without it. This inherently raises an uncomfortable question: are we expanding our capabilities, or are we being replaced? Are we losing control over what we do, or merely freeing ourselves to go further?

In a perfect scenario, expansion and replacement coexist harmoniously. While AI takes control of certain tasks, it also pushes us to explore horizons previously inconceivable. And perhaps therein lies its greatest contribution: it forces us to reconsider new possibilities, something that has always been profoundly human.

What Cannot Be Measured

In the previous chapters, we have talked about productivity, immediacy, efficiency, and how freeing ourselves from tasks can erode our critical thinking and capacity to learn. But there is another dimension at risk of being lost in this celebration of immediacy: that which cannot be measured, that which does not translate into results or efficiency.

Artificial intelligence increasingly pushes us toward a production-oriented logic. In seconds, we can obtain answers, outlines, texts, or images that once required time, dedication, and patience. Yet, at the same time, we risk forgetting an essential aspect of being human: the act of doing without calculating, of experimenting without measuring.

Heidegger warned in The Question Concerning Technology that under the dominion of the Gestell, everything is transformed into a resource to be exploited. Not only do forests become “wood existences” or rivers “hydroelectric energy,” but our own actions and thoughts are reduced to mere inputs and outputs in a productive process. Within this framework, what is not useful seems to have no value.

However, as Nuccio Ordine argues in The Usefulness of the Useless, much of what constitutes the richness of human experience (art, literature, knowledge for its own sake) does not adhere to immediate profitability criteria. Its value lies precisely in being useless from the market’s perspective, yet indispensable for our inner and collective life.

The economy of production, from Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” to today’s algorithms, tends to overlook this aesthetic and gratuitous dimension. A piece of music, a meandering conversation, the pleasure of reading a poem: all of these escape the logic of production and yet give life meaning. What cannot be measured, what does not translate into immediate results, is often what defines and enriches us the most.

Staying Human in the Age of AI

I don’t see AI as inherently good or bad. At its core (and almost by definition) its everyday use tends to amplify who we already are and what we already do. The real risk, I believe, is that it can quietly slip into our routines, becoming invisible and shaping us without us even noticing.

So the question isn’t just how to use AI responsibly, it’s also which parts of ourselves we want to preserve in the process. It’s not about rejecting it, but about embracing it in a way that strengthens our judgment, creativity, and capacity to learn. In our relationship with AI, we must remain the ones who think, the ones who judge, and the ones who teach.